THE MYTHOLOGY OF THE SEVERED HEAD IN SYMBOLIST ART: IMAGES AND IDEAS

LYNDA HARRIS

Lynda Harris has degrees in the history of art from three universities. She has taught extra-mural classes in art and symbolism for London University, and at various venues in and around London. Her book, The Secret Heresy of Hieronymous Bosch was published in 1995.

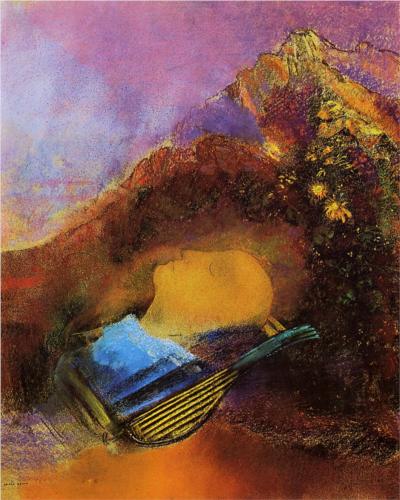

Odilon Redon: ‘Orpheus’. C1903-10. Pastel. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio.

BACKGROUND

The motif of the severed or disembodied head has a very ancient history, and can be interpreted in a number of ways. Though often associated with stories of blood, execution or warfare, it can also have further, more positive layers of meaning. For example, skulls dating from as far back as the Palaeolithic period have been found in shrines in many parts of the world. These heads, belonging to holy sacrificial victims or revered ancestors, were worshipped as oracles, miracle workers and powerful intercessors with the spirit realm.1 This ancient tradition can be deeply ingrained. Particularly strong among Celtic peoples, it continues even today in remote parts of the U.K. such as the Pennines. Faces, carved from local stone, can still be placed in special outdoor spots, or set as guardians inside or outside of houses. Stone heads and human skulls have also been found in brooks and streams, continuing an ancient association with water.2

After Christianity had replaced the pagan religions, the worship of a deified, supposedly living disembodied head was no longer acceptable, and this ancient tradition was only able to continue underground. But some images of the severed head remained popular in art and literature. These included heroic tales, culminating in scenes of victors holding up the decapitated heads of their evil enemies. Such stories could be Biblical (Judith beheading Holophernes or David with the head of Goliath) or mythological (Perseus with the head of Medusa). Histories of saintly martyrs decapitated by evil or corrupt persecutors were also common in the Christian tradition. The New Testament story of the beheading of the John the Baptist is probably the best known of these. But though the Baptist was viewed as a holy figure and the forerunner to Christ, he did not achieve the status of the pagan deities. Several relics, each of them supposedly his head, were kept in various Christian churches. They were believed to cure people, but, though sacred, they were not seen as supernaturally alive, and were not worshipped as gods as the ancient heads had been.

The original historic tradition of the supernatural, oracular head remained underground until the late nineteenth century. It then reappeared in the art and literature of the Symbolist tradition, taking on new characteristics appropriate to the time and place. Adding their own visions and interpretations to the traditional ones, the Symbolists depicted living or godlike severed heads in their art for the first time since Antiquity.3

The Symbolists were particularly drawn to two characteristics of the disembodied head. They were attracted, first of all, by the ancient concept of a living head, revered for its holiness, which continued to sing or speak. With its tragic history, this head became an embodiment of purity and martyrdom. In addition, many of these dramatic tales fitted into another recurring theme in Symbolist art and thought. This was the dangerous eroticism of the femme fatale, who brought about the emasculation or destruction of the male victim through her seduction, treachery or violence. This fear of the feminine may have had ancient origins, interrelated with the image of the Great Mother as a source of both birth and death. According to Kristeva, the vulva, associated with the dangerous decapitated head of Medusa by the Greeks, had also been a source of fear among prehistoric peoples. As evidence she sites various artefacts dating back as early as 30,000 BC.4

EXAMPLES OF SPIRITUAL AND SUPERNATURAL DISEMBODIED HEADS IN SYMBOLIST ART AND THOUGHT

ORPHEUS

Gustave Moreau: ‘Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus on His Lyre’ 1865. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

For the Symbolists, the Greek myth of Orpheus exemplified both martyrdom and misogyny. In the Christian tradition, the myth had been known chiefly as a tale of the Thracian poet/musician’s failed attempt to rescue his love Eurydice from Hades, but the events which followed this are also an important part of the myth.

There are numerous versions of the Orpheus story. The one in Ovid’s Metamorphoses is probably the most widely read. It includes the history of what happened after Orpheus had returned to the earth’s surface. At this stage, desolate after his loss of Eurydice, the godlike poet and singer went to live in the mountains. Here he renounced women, and took up with youths. This angered the wild Maenads or Bacchante, female followers of Bacchus/Dionysus. These women then acted out the ancient mythological story of the dying and rising god. As they had done with Dionysus himself, they turned on Orpheus and tore him apart. The ancient and widespread myth of the sacrificial god has taken many forms, but in all of them the women, in one shape or another, kill and dismember the young demi-god, and afterwards, as benign and motherly females, they begin to worship and mourn him.

These events were rarely depicted or publicised until the Symbolists began taking an interest in them. Influenced by Edouard Schuré’s book The Great Initiates, the Symbolists viewed the tragic Orpheus as an initiate and magician, as well as a great genius of music and poetry with whom they liked to identify. They associated the mysticism, suffering and divinity of Orpheus with those of Christ, another of Schuré’s great initiates. Scenes from the myth which involved the severed head of the dismembered poet/musician had a particular appeal to Symbolist painters. They frequently depicted the head floating down the river Hebrus, resting on its lyre and singing mournfully. According to Ovid, it eventually reached the Mediterranean, and finally, still singing, came to rest on the island of Lesbos. Here, rescued together with the lyre by nymphs or other young maidens, the head of Orpheus became an oracle, visited and worshipped by the Greeks.

Gustave Moreau was the first Symbolist painter to depict the dead Orpheus. His best known painting of the poet’s severed head dates from 1865. Entitled Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus on his Lyre, it shows a benign maiden tenderly carrying the head after it has been rescued. Its eyes are closed as though seeing inward visions appropriate to its future role as a speaking oracle.

The Belgian Symbolist Jean Delville was also drawn to the subject. His oil painting The Dead Orpheus of 1893 depicts the head floating on its lyre over a shallow, rippling sea. The picture is overwhelmingly blue-green in colour, though a closer look reveals other subtle tints. The artist, very aware of esoteric ideas and symbolism, thought of blue as particularly spiritual.5 The water near to the shore is scattered with blue-green seashells, and the lyre is beautifully decorated with small pink and blue pearls. The artist’s wife was the model for the effeminate head of Orpheus, which, like the one in Moreau’s painting, has its eyes closed as though in a trance. According to the myth, the lyre would eventually be carried into the sky by the muses, and would take its place among the stars. Its final destination is hinted at by the reflections of stars which dot the ripples in Delville’s scene.

JOHN THE BAPTIST AND SALOMÉ

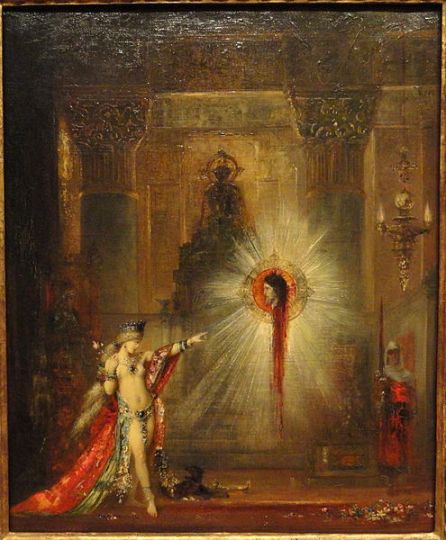

Gustave Moreau: ‘The Apparition’. 1876-77. Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge Massachusetts.

This Biblical story, like the Greek myth of Orpheus, had a special appeal to the Symbolists. The relevant part for them begins when the corrupt tetrarch Herod Antipas kidnaps his deceased brother’s wife, Herodias. Next, after Antipas has renounced his own wife, Herodias marries him. The holy man John the Baptist, disapproving of their actions, criticises Antipas and Herodias. They react by putting him into prison, and soon afterwards, Herodias, planning revenge on the Baptist, asks her young daughter Salomé to dance at the tetrarch’s birthday celebration. Pleased with Salomé’s erotic dance Antipas offers her a reward, and, as is well known, she asks for the head of the Baptist on a platter. Why does she make this particular request? According to the Gospel of St Mark, Herodias tells her to do it. But the Symbolists tended to see the story differently, changing Salomé’s role from innocent (or comparatively innocent) daughter to predatory femme fatale.

Gustave Moreau was the first Symbolist painter to illustrate the story. His sumptuous paintings, with their stress on the corrupt and oriental beauty of the court and Salomé’s role as an exotic femme fatale, had a great influence on Symbolist literature and art. Moreau’s Salome paintings appealed especially to the ‘decadent’ author Joris-Karl Huysmans, who described them in dramatic prose in his book A rebours.6 They also inspired Oscar Wilde, whose play Salome will be looked at further below.

Moreau represented the story of Salomé and the Baptist in numerous sketches, watercolours and oils. The artist’s best known and most influential depictions show her dancing before Herod Antipas in the vast and richly decorated throne room of an oriental palace. In the elaborate and sumptuous oil painting Salomé Dancing Before Herod (1876), the temptress, who is still partially veiled, points a hand at the executioner. Herod watches her, sitting on an elaborate throne surmounted by three statues of Diana of Ephesus. In another version of 1874, the watercolour Salomé with Tattoos, the dancer wears an elaborate headdress and displays her nude body, covered with exquisite tattoos.

Gustave Moreau: ‘Salomé with Tatoos’.1874. Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris.

And in a particularly influential work, The Apparition (1876), the gorgeous but inexorable Salomé points to a vision of the Baptist’s future severed head which is suspended above her, dripping with blood and surrounded by a halo and rays of light. Moreau also depicts later episodes. In Salomé in Prison (1873-76), richly but now modestly robed, she stands out of sight, waiting pensively while the decapitation takes place. Later on, in Salomé at the Column (c.1885-90), she is draped in ornately decorated folds of cloth. Standing statue-like on a pedestal, she displays the Baptist’s decapitated head in a pose reminiscent of Moreau’s Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus on His Lyre.

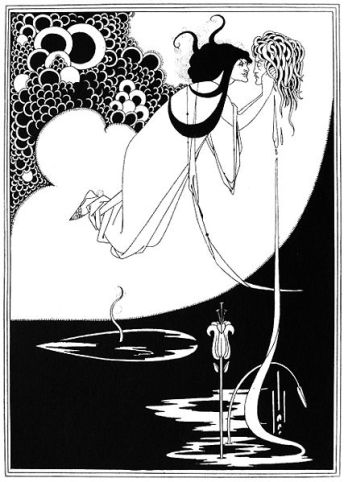

Moreau’s images no doubt influenced Oscar Wilde, who produced his own version of the story in a play of 1891. In his portrayal, Salomé is infatuated with the uninterested Baptist, but is finally able to kiss his lips after she has had him decapitated. Wilde’s play was published in 1894, with some amazing black and white illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley. The best known of these is J’ai baisé ta bouche Jokanaan, whose English title is The Climax. It depicts an oriental and predatory Salomé, with snakelike hair, kneeling in the air. Holding the Baptist’s severed and unenthusiastic head, she is about to kiss his lips.

Aubrey Beardsley: ‘The Climax’. 1894.

DISEMBODIED HEADS IN THE ART OF ODILON REDON

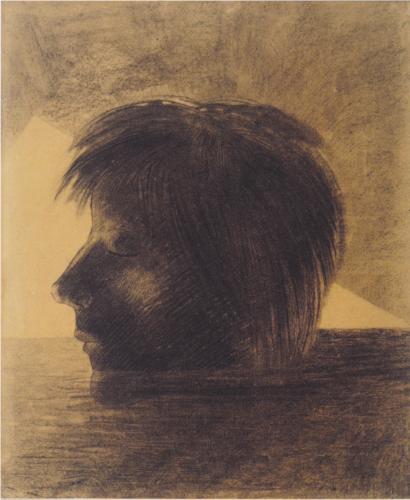

Odilon Redon: ‘Head of Orpheus on the Water’. Charcoal and Pencil. Rijksmuseum Kroller-Muller, Otterlo, Netherlands.

Redon merits a section of his own, as disembodied, living heads appear to have been one of his chief obsessions. He produced a great number of these images. Though some of them depict decapitated heads, the majority represent beings which have always existed independently without bodies. These creatures, which are frequently airborne, tend to look sepulchral and ghostly. Though not gruesome, they are in no way cheerful. Most depictions of them, known as his ‘noirs’, are charcoals and lithographs, executed in black and white. Though disembodied heads populate his works throughout his career, most date from his earlier period, beginning in the 1870s.

Redon did not explain his images, leaving them to the interpretation of the viewer. Nevertheless, it is known that he had esoteric interests, and was influenced by Theosophy and Schuré’s book The Great Initiates.7

According to the thesis of R.J. Mesley, Redon was affected not only by the above esoteric theories, but also by Orphic ideas of the soul’s fall and entrapment in matter. The artist’s sources would have included various Parisian contacts, as well as the works of Symbolist authors such as Baudelaire. In Mesley’s Orphic interpretation of Redon’s works, many of the artist’s numerous disembodied airborne heads (most notably those in his 1879 album of lithographs, Dans le Reve), are images of souls which have fallen from the heavenly world into the world of matter. These souls float in the sublunary realm between the moon and the earth, moving between physical incarnations and sojourns on the moon. Eventually, with the help of a feminine angel figure, the souls will free themselves from the temptation to reincarnate in the physical world, and move on to a more heavenly area.

Odilon Redon: ‘Germination’ from ‘Dans le Reve’.1879. Lithograph.

Redon also depicted the decapitated head of Orpheus himself. In two noirs of the early 1880s, the initiate’s head floats on water, without his lyre. Though these scenes are dark, areas of light illuminate the face and parts of the sea. The floating heads have a look of mysticism and concentration, whether their eyes are closed or open.

During the 1880’s Redon began producing works (usually pastels) which were as luminously coloured as his noirshad been dark. Among these is a much later and better known example of the head of Orpheus, dated 1898. In this pastel the lyre and head of Orpheus are washed up on a rocky shore, illuminated by a bright blue and purple sky behind the flowery hills. The initiate’s eyes are closed, and he seems to be engrossed in his inner visions.

Among Redon’s numerous depictions of severed heads there are also, not surprisingly, a number which represent John the Baptist. John’s head can be shown independently on a dish, or in a scene together with Salomé. In a charcoal of 1877 entitled Salomé, for example, the head held on a platter by the lovely yet heartless dancer has features very similar to Redon’s own.9

Salomé is shown again, but very differently, in Redon’s very individual version of Moreau’s ‘The Apparition’dated 1883. Here, she becomes a dark, quiet and apparently menacing figure, standing on the left side of the scene. The stress in this charcoal drawing is on the head of the Baptist, which floats in front of her against the backdrop of a dark doorway. The ghostly and spectral head is surrounded by rays, and partially covered by a dark disk reminiscent of a black sun. Redon’s paintings often have themes of darkness versus light, and it is possible that the artist is hinting here at the attack of corrupt and evil forces against the spirituality of the Baptist or (on a more universal level), the soul of humanity.

In a later coloured pastel by Redon dated 1893, two women in vibrant blue hooded cloaks stand looking down at a holy severed head which radiates light. This work is normally given the title Salomé, but, as Mesley says, the scene might also represent the head of Orpheus, attended by two muses

Odilon Redon: ‘Salomé’. C1893. Pastel. Kunsthalle Bremen, Bremen, Germany.

CONCLUSION

As this article will have shown, the significance of the severed head is particularly complicated, and can be understood in various ways, depending on individual interests. It can be an image of vengeance and horror. It can also represent holiness, purity or (in the esoteric interpretation), the soul. On other occasions, it plays a central part in the story of a dangerous femme fatale. Between them, the Symbolists managed to revive some of the more ancient meanings, and to include all of them into their art.

1. See Julia Kristeva, The Severed Head: Capital Visions, New York, Columbia University Press, c.2012.

2. David Clarke with Andy Roberts, Twilight of the Celtic Gods, An Exploration of Britain’s Hidden Pagan Traditions, Cassell PLC, London, 1996, pp.124ff and 138ff.

3. Dorothy M. Kosinski, Orpheus in Nineteenth-Century Symbolism, Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, c.1989, p xiv.

4. Julia Kristeva, The Severed Head, pp.29ff.

5. Francine-Claire Legrand, Symbolism in Belgium, Brussels, Laconti, 1972, p.27.

6. A rebours is translated into English as Against Nature or Against the Grain.

7. See Fred Leeman, ‘Redon’s Spiritualism and the Rise of Mysticism’, pp.215-221, in Odilon Redon 1840-1916, exhibition catalogue, Chicago, Amsterdam and London. Thames and Hudson, 1994.

8. For more of this interpretation see Roger James Mesley, The Theme of Mystic Quest in the Art of Odilon Redon, PhD Thesis, Department of Art History, University of Toronto, 1983.

9. Douglas W. Druick and Peter Kort Zegen, ‘Taking Wing, 1870-1878’, p.86, in Odilon Redon 1840-1916, exhibition catalogue, Chicago, Amsterdam and London. Thames and Hudson. 1994.

10. Mesley, The Mystic Quest, Chapter One, pp.42-43.

If you would like to correspond with the writer of this article please enter your details by clicking here: CONTACT US