‘VISIONS AND MYSTICISM’

ELEANOR VERE BOYLE (EVB)

Lynda Harris

Lynda Harris is the author of The Secret Heresy of Hieronymus Bosch, a book on Cathar art. She has also written articles on Symbolist painters such as Jean Delville and Evelyn De Morgan She holds Art History degrees from Bryn Mawr College, Boston University and the Courtauld Institute of Art.

EVB ‘When Shadows Fall’

BACKGROUND AND BIOGRAPHY

Born and married into a traditionally Anglican upper-class family, Eleanor Vere Gordon Boyle (1825-1916) is best known as a book illustrator. Specialising in children’s stories and gardens, she managed to develop her artistic talents and achieve success, despite family restrictions. But beneath her outwardly traditional surface she was a visionary and also something of a psychic. This is revealed in some of her illustrations, as well as her lesser-known art.

The youngest of the nine children of Albinia Cumberland and Alexander Gordon, EVB was known for her sweet nature, humour and vitality. At the age of twenty, following the conventions of her milieu, she married the Reverend Hon. Richard Boyle, the youngest son of the Earl of Cork. The couple settled on the Boyle family estate in Marston Bigott Somerset, where Richard took up the family living. Their first daughter was born within a year of their marriage, and by 1854 they had five children – two girls and three boys.

EVB ‘Self-Portrait with Young Children’

Though Richard and Eleanor took trips to Europe, particularly the South of France, they spent the majority of their time at Marston. Richard continued as rector of the parish until 1875, when he retired and he and Eleanor left the rectory and moved to Huntercombe Manor, a seventeenth century house near Maidenhead in Buckinghamshire. Now a mental hospital for young people, the manor still retains some of the gardens which the Boyles created there.

As her life progressed, EVB was increasingly affected by the illnesses and deaths of people she was close to. Her much-loved mother died in 1849, when EVB was only twenty four years old, and her elder sister Alba died soon after, in 1854. By 1860, EVB’s first-born daughter Nellie, who had begun life happy and healthy, had contracted tuberculosis. Nellie died in 1871, at the age of twenty five, after a long decline. Later blows followed during the course of EVB’s long life. In 1878, when she was fifty three, her husband Richard had a disabling stroke. She spent much of her time caring for him, until he died eight years later. A few years afterwards, during the early 1890’s, she lost three of her closest friends: her distant cousin the artist Lady Louisa Waterford, another cousin, Mary Boyle, and Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, the author and art historian who was married to Sir Charles Eastlake, director of the National Gallery. Finally, she had to endure outliving two of her sons, who died in 1909 and 1914. These unhappy events caused her to be concerned (perhaps to an unusual degree) with the question of life after death. As we will see later, she developed a preoccupation which affected the subject matter of her works.

Though EVB does not appear to have discussed her concerns about the afterlife with her family, she does seem to have shared them with the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson. Tennyson, already a family friend, became a relative in 1884, when his son Hallam married EVB’s relative Audrey Boyle. It is likely that many of EVB’s visionary paintings were affected by her contacts with the poet. Their friendship had begun sometime before 1860, as will be seen below. Tennyson (along with the Pre-Raphaelites) also influenced her interest in the Middle Ages and her frequent depictions of people in Medieval dress.

ART AND DEVELOPMENT

Other aspects of EVB’s life also affected the development of her art. Though she loved living in the countryside and her family was privileged and well connected, EVB’s upper class background was not entirely without its disadvantages. Her great-great granddaughter Margaret de Wend Fenton, who has made a study of EVB and her family, tells us that, despite the fact that her family recognised her unusual talent, the possibility of professional art training was never even considered. Her tutoring came instead from her mother and her sister Alba, both of whom had an ability at drawing. In a letter written in about 1833, Alba (who was nine years older than EVB) told her brother ‘I am quite as fond of drawing as ever, and I make Ella [EVB] practise every day’.1 Later, when she was a young married woman, EVB made some attempts to paint in oils and model in clay. She did not get very far with these, however, as her family made it clear that they were not appropriate media for a lady.2 Unlike Evelyn De Morgan, who also had aristocratic connections, EVB did not rebel against these restrictions. Instead she worked within them, specialising in watercolours, graphics and book illustrations. During her early twenties she was able to develop her skill at engraving without leaving home. Her tutor was Tom Landseer, the brother of the well-known Victorian artist Edwin Landseer.3

Though EVB was a very enthusiastic mother, she differed from many of her contemporaries in that, along with her commitment to her children, she continued to retain a serious and professional approach to the art she was permitted to practice. She wrote the texts of some of her illustrated books, especially in later life, after her move to Huntercombe Manor. During this later period, while a number of her works reflect her preoccupation with death and the next world, she also wrote books on gardens. She became especially well known for these in later life. In her younger years, when most of her works were related to children, she used her own offspring as models. She incorporated her sketches and landscapes into illustrations for nursery rhymes, fairy tales, and other children’s stories. Her earliest book, Child’s Play, was published in 1852. This was the first U.K. publication in which nursery rhymes were given high quality illustrations, and it received enthusiastic reviews.4 At this date, EVB was also the only female book illustrator of any importance. Her extended family was not very happy about her pioneering work, however, and, as Margaret de Wend Fenton has related in a personal communication, she had to endure their jokes and their condescending references to her works as ‘Ella’s fancies’.

The wider world was more appreciative, however. The books sold well, and when a parcel containing her etched illustrations for her second book, The Children’s Summer, was sent to John Ruskin in 1852 by a mutual friend, his response was enthusiastic. Ruskin wrote back immediately, saying

I never saw anything in modern art approaching them – except the finest thoughts of Millais and Hunt. These etchings have also a grace and freshness which their works have not.5

Another positive response to her work came from EVB’s friend John Everett Millais. According to a letter from Rossetti to W.B. Scott, Millais had suggested that EVB and her cousin Lady Louisa Waterford join a projected sketching club, along with various members of the P.R.B. Although the sketching club never materialised, it is significant that EVB and Waterford were described in the letter as ‘promising artists, above the rank of amateurs’.6

In April 1902, a collection of EVB’s originals, most of which had been produced between 1849 and 1880, was exhibited in the Glass Studio at Leighton House, and given the title Sketches, Dreams and Drawings. In his preface to the catalogue, William Hardinge commented ‘To those who have once come under this magic, it is a spell as unmistakable as Blake’s or Rossetti’s.’ 7 He was particularly impressed by her illustrations to Tennyson’s The May Queen, as well as ‘two pictures shown in the Grosvenor Gallery thirty years ago’ (unfortunately, he gives no titles for these). He also said that her illustrated book Days and Hours in a Garden stood out from all other books.8

But, though the exhibition was successful enough, not all of the critics who saw it agreed with Hardinge’s positive comments. EVB accepted the views of one, who remarked that her work belonged to another, earlier age. On the other hand, she was less pleased at being described as an artist who ‘hopped about from one thing to another’.9 She was especially upset by the critic who compared her to Kate Greenaway. Though this man’s insensitive simplification may have been nothing more than a response to EVB’s many depictions of children, EVB reacted angrily. She expressed her views forcefully, saying ‘She [Greenaway] was very nice, very pretty indeed, but could she enter into and seize the heart of even a bit of drapery? Far less of God’s creatures of beast and feather and poetry, and – divinest of all – of pure colour? Of course I cannot dare to say that I did, but I’m a long way nearer art than Kate Greenaway (poor dear woman) was.’ 10

MYSTICISM AND VISIONS

EVB was making a valid point when she placed herself on a different level than Greenaway, but the main contrast between the two artists has nothing to do with technical expertise. The chief difference between them has more to do with depth and spirituality. Although EVB had a practical side and was involved in the domestic world around her, she was also a mystic and visionary who admired Blake. As she said in an undated letter to her good friend Lady Eastlake,

Blake is marvellous as only he can be. In some (many) of his drawings there is a feeling, a grasp of imagination as impossible for the present day mind to understand as to imitate – the feeling in them is as fine as possible – but I can understand how the people sneer, and say ‘he was mad’.12

Like Blake, EVB was aware of not only of the spirituality of the natural world, but also of the worlds beyond. All through her life she had seen visions and apparitions, which she recorded, along with her vivid, and sometimes strange dreams, in her letters, journals and diaries.

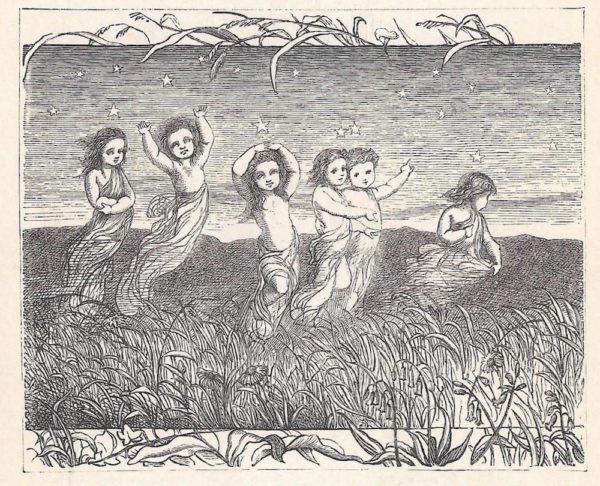

In one of her diary entries EVB describes how, as a child, she had calmly accepted seeing a white angel blowing a golden trumpet in her dark bedroom. She also saw a train of ladies dressed in yellow moving along the nursery wall, and, on another occasion, noticed two goddesses sitting serenely on a cloud above the family garden.13 Later, as a young adult, she visited the churchyard at Maryculter near to Ellon, her father’s Scottish castle. Here, as she puts it, she communed with ‘her friends the Invisible Host in the City of Silence.’ 14 She also reported seeing ghosts in various other locations which she visited, and had visions of nature spirits when walking in quiet, rural places. Some of these nature spirits are illustrated in her book In a Fir Wood inspired in 1865 by a solitary walk in a wood near to Ellon. Here she writes ‘Have I not seen – in dreams at least, and with the eyes of my soul – the spirit who haunts this magic round? Do I not know her well?’15

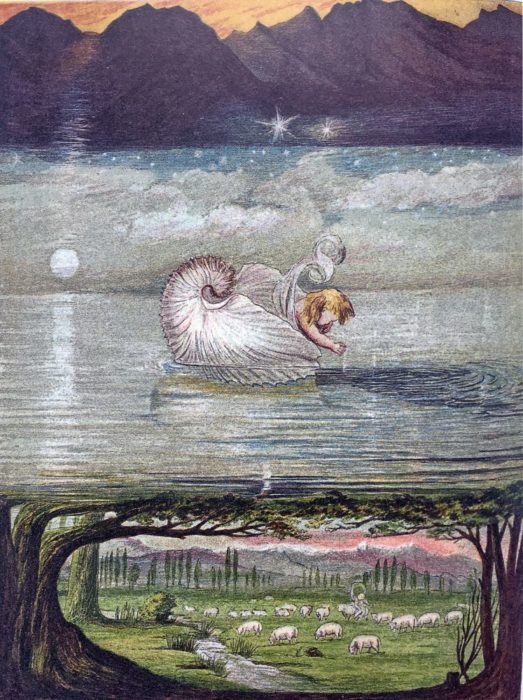

A Golden Boat on a Great, Great Water from Carobé’s The Story without an End

EVB ‘A Golden Boat on a Great, Great Water’

EVB’s visionary abilities are also exemplified in a beautiful colour picture titled A Golden Boat on a Great, Great Water. This is the most striking illustration in the series that she made for The Story Without an End, a contemporary fairy tale written by the German author Carobé. EVB worked on the illustrations for several years. In the end, twenty of her watercolours were chosen for the English edition of 1867, translated by Sarah Austin. The picture A Golden Boat on a Great, Great Water, in Chapter III of the book, depicts a series of multi-layered landscapes. Its colours, clear, fresh and glowing in the printed book, were apparently even more beautiful in the watercolour original.16

The text of Chapter III describes a child who dreams that he is sailing in the boat underneath the moon and ‘countless stars’. He tries to catch them, then realises that he is reaching for their reflections in the water as they are above him. His dream then takes him flying up among the clouds, which he sees as sheep. These dissolve in his hands, and he wishes he was ‘down again in his own meadow, where his own lamb was sporting gaily about.’ Then, before he wakes up, he dreams he is falling down into dark, gloomy mountain caverns.

EVB’s illustrations include all the elements of Carobé’s text, but do not depict it literally. Instead of following the events of the story as they occurred, she creates a dreamlike scene which is made up of several layered worlds. The gloomy mountains are at the top, surmounted by a hot yellow sky. At their feet, doubling as both a lake and a firmament, is the dark blue sky which contains the ‘countless stars’. It is edged at the front by a bank of clouds. The moon floats just below these clouds, not far above a second, lower lake. The child (who is modelled on EVB’s youngest son Algy) sails on this wide, shining sheet of reflective water in a boat which seems to be a combination of swan and seashell. He reaches into the water, trying to catch the starry reflections. He seems unaware that this large and shimmering lake surmounts an almost bubble-like earth world. This world, the lowest of the three, is complete in itself. It is enclosed by trees, whose leafy branches meet and join at the top, forming a protective circle. Within the circle, sheep graze on a green meadow, and poplars and snowy mountains can be seen in the far distance, along with the earth’s own separate sunset sky. The three worlds in this painting are all independent, yet the picture as a whole is unified, with the child as its central focus.

Where did this visionary image come from? Hovering near to the paranormal but not treating it overtly, the beautiful and fascinating scene brings to mind the layered universe which was integral to the world views of Spiritualism and (at a later date) Theosophy. As far as we know, however, EVB was never committed to any of the alternative movements. If she was inspired by them, consciously or unconsciously, she does not say so, and her vision does not seem to be directly related to any set of beliefs, Christian or otherwise. The painting does have something in common with Rossetti’s Blessed Damozel, however. Rossetti’s work, executed about eight years later, depicts a youth reclining on the level of the earth. He looks up at his deceased beloved, located in the separate heavenly plane above his head. If there was any connection between the two works, the dates show that the influence would have come from EVB to Rossetti.

The chief source of EVB’s scene is probably her own visionary imagination. A partial hint of this is found in one of her unpublished books, where she refers to visions of similar images of layered worlds seen in cloud formations. The boy who sees them has been left behind in England, cared for by the servants, while the rest of his family travelled abroad. According to a personal communication by Margaret de Wend Fenton, this story was based on her own worries over leaving Algy, who had been too young to accompany the rest of his family on a long trip to France.

When Shadows Fall

EVB ‘When Shadows Fall’

Another lovely vision, which exemplifies the delicacy and sensitivity of EVB’s work at its best, is entitled When Shadows Fall. Though this picture brings the Symbolist style of the 1880s and 1890s to mind, its date (1869) shows that it was executed earlier than this. Typically of EVB, it is individual, and not tied to a single school. It exists in two versions, as a watercolour (now in a private collection) and as a print, published as a part of EVB’s Dream Book.17 The picture may seem at first to be simply a meditation with no particular symbolism, but its appearance gives the wrong impression. Instead, as we will see soon, it is likely that the work is putting across a particular message which has connections with EVB’s ideas about death and the hope of the next world.

When Shadows Fall depicts a young woman in a long black dress walking pensively beside a smoothly reflective river. She is accompanied by three large white swans. Beyond the river, a misty and delicately painted landscape of woods and meadows stretches into the distance. In the watercolour, this landscape is executed in muted blues and greens, with a brown wash. In the printed version it is a balance of blacks, greys and whites. Margaret de Wend Fenton, discussing the painting, has said that the scenery is based on the grounds of Hampton Court, and the model is EVB’s good friend and distant cousin, Lady Louisa Waterford. Waterford can be identified by her tall, slim and dignified figure, as well as her hair, done in a large and high bun.

The print of version of When Shadows Fall, included in the published Dream Book, is accompanied by two poems, one by Schiller and the other by Tennyson. Both describe a beautiful and adored, but unattainable and disdainful lady. Tennyson’s poem is the nearest to the painting:

By the lake she paces stately

In her robes of sable hue.

From the tender green-sward brushing

Slowly, as in scorn, the dew.

In her soul is no relenting,

Though her face is wondrous fair,

She would trample on my passion,

As she treads on daisies there.

In her train, like loyal subjects,

Stately swans attendant glide,

Dazzling white their downy plumage,

Arched their snowy necks of pride.

Wastefully she scatters bounties

On these vassals of her land,

I would lay my life before her

For one crumb from her white hand.

Though Tennyson’s poem is illustrated closely in EVB’s picture, her scene contains further layers of symbolism not found in either poem. The paintings’ muted colours, as well as its title When Shadows Fall, associate the scene with twilight, and indicate that the woman, despite her beauty, is now aging and meditating on death. Though she still appears young in the picture, Wend Fenton has also pointed out that Louisa Waterford was aged fifty eight in 1869, and was approaching the end of her life. She had also been widowed early, and her black dress is an indication of her widowhood. She could be thinking of her husband’s death, as well as her own. She looks towards a line of white stones on the other side of the river. These could be gravestones, or subtly shining lights, hinting at post-mortem survival. Most likely they are both.

A Book of The Heavenly Birthdays

As time passed, and more tragic deaths occurred in EVB’s family, her preoccupation with the after world increased. Although, by necessity and probably inclination, she saw the afterlife in terms of conventional Anglican religion, she was also aware that it was a universal concern, and was viewed similarly in many countries. Her increasing interest in this theme is exemplified by her anthology A Book of The Heavenly Birthdays. Dedicated ‘To the bright memory of my mother, Albinia Elizabeth Gordon, and to those others, dear and unforgotten, who, in following her, set their faces homewards, and long since anchored in the quiet havens’, this is an anthology of poems on the subject of leaving this world and entering the next one. EVB began collecting and illustrating the works in 1892, and includes poems which are relevant to various cultures and traditions. One example is a scene illustrating Klopstock’s words ‘Thou Shalt Arise, my Soul’ , in which a butterfly emerges from a cocoon. In another, entitled ‘Eternal Father strong and sane’, a ship is sinking into a turbulent sea.

EVB Illustration from ‘A Book of the Heavenly Birthdays’

The sun on the distant horizon may be either rising or setting. This anthology was published in 1893, and the notebook containing EVB’s original drawings was exhibited in Brighton at around the time of the book’s publication.

EVB AND THE SPIRITUALIST MOVEMENT

In 1886, a few years before she had begun to collect the poems for A Book of The Heavenly Birthdays, EVB records an occasion when she went to a Spiritualist séance. She did this while living with her daughter Bella in London, during the winter after her husband’s death. The séance took place at a private house, and, according to her diary, ‘it was all very curious and new to me.’ She describes the medium, Miss McAndrew, as ‘a bolt upright youngish lady with clever, strange looking eyes.’ The small group of sitters plunged at once into talk of what EVB sums up as Mysticism and ancient religions, and, after dinner, they began to ‘play Planchette’. Later, when the door was locked and the room made dark, EVB felt that the air was full of spirits. She saw strange lights, and her whole body began to tingle. A special message was written for her, saying ‘The blessing of those who are passed away rest on you’. This touched her, and brought tears to her eyes.18

There are no records of whether or not EVB went to any further séances. It may well be that she did not. Strictly traditional Christians took the view that all souls, apart from the restless and the earthbound, were confined to their own realms. These strict beliefs were not adhered to by everyone, but, according to Wend Fenton, EVB’s family would have objected particularly to the calling back of the spirits of the dead, and she is likely to have gone along with this.

Spirit Visitations in EVB’s Works: The May Queen and Beauty and the Beast

Though EVB would have avoided conscious attempts to call back the departed, her mysticism and psychic abilities could well have led to personal and spontaneous contacts with beloved family members whom she desperately missed. This possibility is hinted at in two of her best known book illustrations, both of which depict private contacts between bereaved mothers and daughters.

One of these two illustrations depicts a scene from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s tragic poem, The May Queen. Though Tennyson was not yet EVB’s relative through marriage, she was already friendly with him when he wrote The May Queen. She asked for and received his permission to illustrate the poem, which was very popular among Victorian readers. She worked on the preliminary drawings throughout 1860, and the edition with her black and white illustrations was published in 1861.

The May Queen tells the story of a proud and supercilious girl who, after having been voted Queen of the May, becomes ill and spends much time and many words anticipating her inevitable early death. The heartrending story appealed to EVB, who used her consumptive daughter Nellie as the model for the young girl. This was not a coincidence, for, as Wend Fenton puts it, ‘One wonders if the mother had specially undertaken this work to try and prepare herself for [Nellie’s] inevitable tragic ending’.19

Tennyson was not a conventional believer. He was interested in Spiritualism and other paranormal ideas. It is significant, in view of this, that his poem The May Queen reflects concepts which are more reminiscent of the Spiritualist tradition than conventional church teachings. As her end approaches, the May queen says that she will come often to be with her mother after her death, even though she does not expect to be seen. EVB depicts one of the daughter’s periodical returns to earth in the illustration on p.23 of the published version of the book.

EVB illustration to Tennyson, The May Queen, p.23

Here, presumably invisible to her family, the semi-transparent daughter, is shown sitting by her mother and sister during a descent from the heavenly realms. EVB’s depiction of her visit reveals that, like Tennyson, she is thinking in terms of spirits travelling to see their families, even if they cannot be seen by the bereaved.

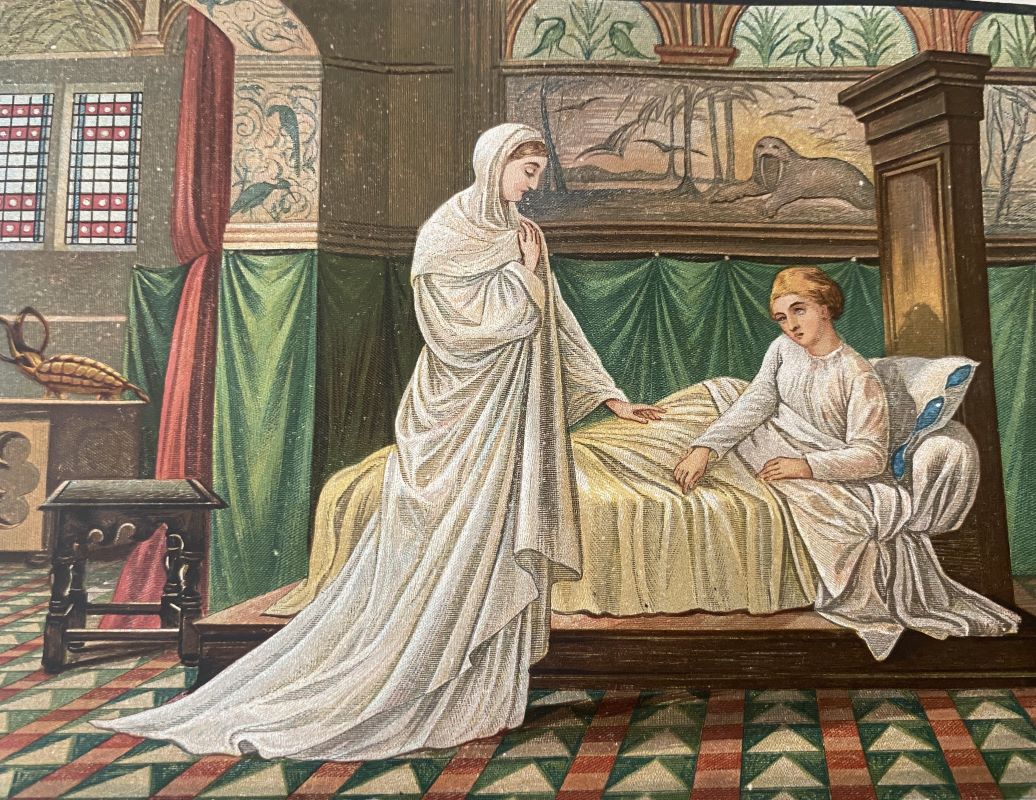

EVB Illustration from Beauty and the Beast

EVB’s second depiction of a spirit which, in this case, seems to be visible, is found in her Beauty and the Beast: An Old Tale New-Told. Published in 1875, this is a retelling of the ancient traditional fairy story. EVB wrote the text for this edition, as well as designing the colour illustrations. When the book was nearly finished she took it with her on a visit to Knebworth, the country house of the writer and occultist Lord Bulwer-Lytton. She had been in correspondence with Bulwer since at least 1866, although a letter she sent from Knebworth to her husband Richard gives the impression that this was the first time she had actually met him. She showed her illustrations to Bulwer, along with the rest of his house party, and was pleased with their interest in the Beast, with his long ‘teeth’.20

Nearly all of EVB’s illustrations follow the traditional Beauty and the Beast story closely. Just one episode, which depicts a visit from Beauty’s deceased mother, is unusual. In this scene Beauty sits up in bed in an elaborate room, in which Renaissance décor is combined with Byzantine mosaics. The walrus-like Beast is depicted in a fresco on the wall above her bed. The mother’s spirit has come to comfort Beauty during her difficult and lonely stay in the palace of the Beast. She stands with her head lowered, and one hand held out towards her daughter. Beauty is clearly aware of her, and may even be able to see her. The spirit is swathed in abundant draperies, which seem to be made of the same material as the voluminous sheets on the bed. This episode is original to EVB, as the traditional tale says little about her mother, apart from implying that she has died. A printed edition of the story, published in eighteenth century France and written by Madame Barbot de Villeneuve, does say more about the mother, but is also different from that of EVB. In Villeneuve’s version, Beauty’s mother turns out to be the cruel fairy who had first enchanted the Beast.21

In EVB’s story, the mother is not cruel, but is instead a gentle, and positive presence visiting from the next world. EVB, who lost her own beloved mother when she was twenty four years old, must often have missed and needed her. It is very possible that she, like Beauty, sometimes felt she was in contact with her mother’s departed spirit. Though the pale and abundant draperies of Beauty’s mother have an interesting resemblance to the ectoplasm of Spiritualist séances, this may be coincidental. EVB presumably knew about ectoplasm in 1875 when she executed the illustration, but, at least until her husband’s death, she would not have investigated it. As we have seen, she did not visit a medium until the winter of 1886, soon after she had been widowed. This was more than ten years after the publication of her Beauty and the Beast.

VIRGIL AND THE QUESTIONS OF REINCARNATION AND THE PRE-EXISTENCE OF THE SOUL

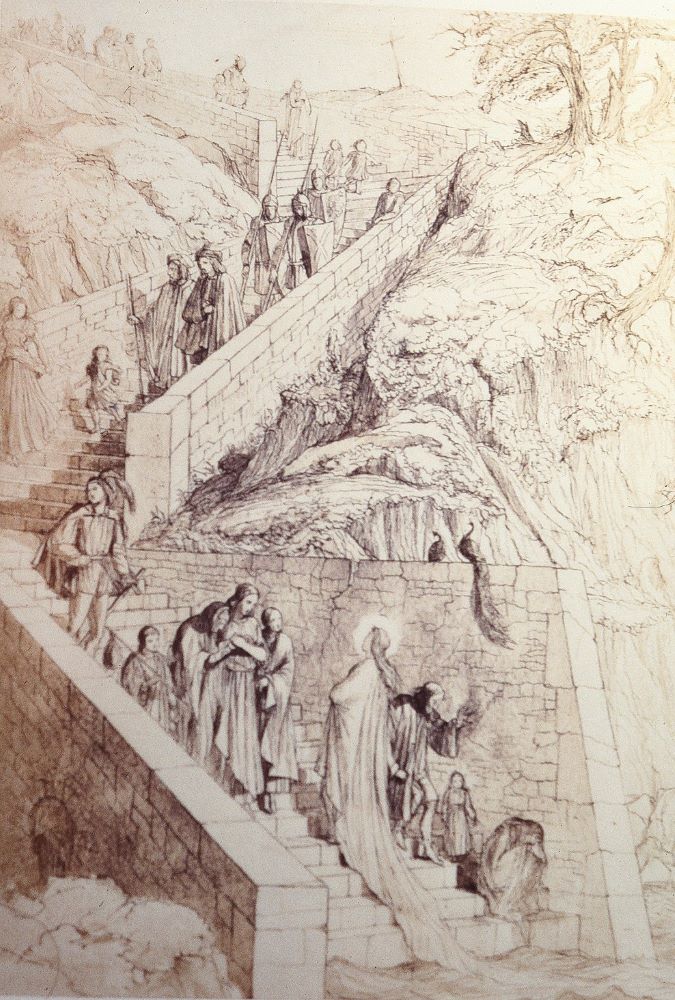

Facilis Decensus

EVB ‘Facilis Decensus’

Another, very different work by EVB, which also edges away from conventional Christianity, is included in a book of drawings dated 1855. Seven years later, in 1862, it was reproduced as an engraving, and included in a short picture book called Waifs and Strays from a Scrapbook. The drawing’s title, Facilis Decensus, identifies it as having a connection with Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid

This part of Virgil’s poem raises questions to do with reincarnation and the pre-existence of the soul. The full quotation referred to by EVB is from lines 126-129:

Facilis decensus Averno; …

Sed revocare gradum superasque evadere ad auras,

Hoc opus, hic labor est

This quotation, translated as ‘the descent to Hades is easy….but to retrace your steps to the upper air is difficult work’, can have two different interpretations. Exoterically, it can be understood as saying that it is difficult for a shade to return to the earth, once it has gone to the world of the dead. Esoterically, the meaning is very different. In this interpretation, the physical world is seen as ‘Hades’, and the souls which descend into incarnation in its realm of shadows will be trapped in a cycle of birth and death. It is difficult to escape from this into the ‘upper air’ (the spiritual realms).

EVB’s Facilis Decensus clearly follows the esoteric interpretation, which views birth on earth as an unhappy event. It depicts a procession of people, dressed in fifteenth century clothes and varying in years from old age to childhood, walking down a winding stairway. Most of them look cautious and apprehensive. A body of water is visible at the foot of the stairway, and all but one of the figures are walking towards it.

Though EVB’s winding stairway brings Jacob’s Ladder to mind. It is clearly a route between earth and the higher levels, and has some connection with the biblical image. As Wend Fenton has said in a personal communication, EVB had been struck by Jacob’s Ladder from an early age, and wrote a note in a scrapbook referring to a dream of her brother’s, in which he saw angels ascending and descending it.

In EVB’s version the majority of the figures are descending. Only one of them, a robed female reminiscent of one of the souls in Blake’s ‘Jacob’s Ladder’, is shown ascending the stairs. She looks brighter than the others, and her face is turned raptly upwards. Her long train still drags in the wet, revealing that she has been in the water herself, and is now leaving it behind. She contrasts with a hunched figure sitting in a despairing pose at the foot of the stairs, just above the water. Presumably this water represents the River Lethe, as in Virgil, but just what does it signify to EVB? Her figures, especially the ones on the lowest level, are not happy about entering it. The ascending figure, in contrast, looks upwards towards a more mystical realm. Clearly, the water is not a desirable element in which to bathe.

As the entire scene shows, a contrast is made between physical birth into a world of woe, and the hope of an escape from earthly existence into a higher realm. The anticipation of an eventual heavenly destination is enforced by two peacocks, traditional Christian symbols of eternal life. Their position on top of the wall above the ascending figure and a man next to her who is moving downwards, indicates that both of them will one day reach salvation.

But is this simply a depiction of the Christian promise of heaven, after a difficult life in ‘the vale of sorrows’? The maturity of most of the figures which descend the stairs implies that there is an added esoteric significance here. According to traditional church teachings, each soul is created new at birth. EVB’s unusual depiction of souls entering earthly life not as innocent, newly created infants, but as adults or half-grown children who look experienced and are already dressed for their roles in the life to come, is therefore odd and unusual. It suggests that they have been planning their future lives before they are born, and brings the concepts of reincarnation and/or the pre-existence of the soul to mind.

This concept of the soul’s pre-existence in heaven was a sort of half-way house to a belief in reincarnation. The idea of repeated incarnations, and entrapment in the cycle of birth and death would have been strongly disapproved of in EVB’s milieu, and the concept of pre-existence would have been more acceptable. She could have discussed these subjects with Tennyson, whom she may well have known by this date. (Facilis Decensus was executed in 1855, and, as we have seen, she was already on good terms with Tennyson in 1860, when she received his permission to illustrate The May Queen.) Tennyson’s support of the concepts of reincarnation and pre-existence is shown in at least three of his poems: Early Sonnets No. I; De Profundis, and The Two Voices.22

EVB AND EVELYN DE MORGAN

EVB ‘Mermaids’

EVB’s interest in the contrast between the spiritual and earthly worlds would have given her something in common with Evelyn De Morgan, a much younger painter who, unlike EVB, had insisted on studying oil painting at the Slade despite her own aristocratic connections. From about 1887 De Morgan used her abilities in oils to express themes of Spiritualism and the aspiration to a brighter realm. These subjects were also of great interest to EVB. Did the two painters meet and discuss their mutual preoccupations? If so, their encounter could have taken place during the winter of 1886-87, when EVB was staying with her sister in London. Evelyn normally spent her winters in Florence, but this year she would have been in London preparing for her wedding to William De Morgan in March 1887.

Is there any evidence that the two artists met, or at least saw each other’s pictures? If we compare EVB’s watercolour Mermaids and De Morgan’s oil painting The Sea Maidens the resemblance is surely more than coincidence.

Evelyn De Morgan ‘The Sea Maidens’

In both paintings a comradely group of long-haired mermaids emerges from the sea in a line. In both, the water spirits share a friendly, tactile relationship, and in both the upper parts of their scaly tails are visible above the water. Evelyn De Morgan’s painting, dated 1885-6, was exhibited at the Institute of Painters in Oil Colours in 1886/1887, probably more than twenty years after EVB had executed her Mermaids. Though EVB’s work is undated, its estimated date is based on EVB’s engraving of a similar line of cavorting cherubs published in 1861, in The May Queen.23

EVB ‘Cavorting Cherubs’

If EVB’s watercolour was painted soon after her engraving, it would have been she who influenced Evelyn De Morgan.

Though it is unlikely that we will ever know the full history, the resemblances between EVB’s illustration and De Morgan’s oil painting are intriguing. As with the possible connection with Rossetti (see above) it indicates that EVB had a greater influence than is usually realised on the works of painters whose pictures were more frequently exhibited, and whose names were more widely known.

1916

EVB continued living at Huntercombe Manor and paying visits to relatives until 1916, when, at the late age of 91, her health began to fail. That summer, at her family’s suggestion, she went to Brighton with her companion Ginny in hopes that the sea air would bring an improvement. It was here that she died soon before her family arrived, giving her companion what Wend Fenton describes as ‘one last radiant embrace’.24

ELEANOR VERE BOYLE: NOTES

1 Margaret de Wend Fenton (great-great granddaughter of EVB), unpublished biography of EVB, version 2, N.D., p.30.

2 See EVB, letter to brother Bertie quoted in Wend Fenton 2, p.49, and Wend Fenton 2, p.52.

3 EVB, letter to Lady Eastlake, quoted in Margaret de Wend Fenton, Unpublished Biography of EVB, version 1, N.D., p.6.

4 Wend Fenton, personal communication.

5 Letter from John Ruskin to Morier, 14 Nov. 1852, quoted in Wend Fenton 2, pp.47f.

6 Millais, J.G., published collection of his father’s letters, in which he quotes a letter from J.E. Millais, referring to an earlier epistle of 1854, from Rossetti to W.B. Scott. See Wend Fenton 2, p.58.

7 William Hardinge, preface to catalogue of Leighton House exhibition, April 1902, quoted in Wend Fenton 2, p. 118.

8 Hardinge, as in Note 7.

9 EVB, quoted in Wend Fenton 2, p.119.

10 EVB, quoted in Wend Fenton 2, p.120.

11 These written records, previously in the possession of Margaret De Wend Fenton, are now in the collection of [GET]

12 E.V.B.’s comments on Blake are from an undated letter in the possession the family of M. de Wend Fenton, contained in an envelope entitled ‘My letters from Spain to Dearest Lady Eastlake, the only friend of my soul and my heart that I ever had’.

13 For these and other childhood visions see Wend Fenton pp.27f.

14 See McGarvie, Michael, ‘Eleanor Vere Boyle writer and illustrater, Life, Work and Circle’, Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society (London), New Series, Vol. 26, 1982, pp.110ff.

15 EVB, In the Fir Wood, London: Macmillan, 1866, p.8.

16 The original watercolour illustrations for the Story Without an End were sold by M. de Wend Fenton to the dealer Jeremy Maas. His son still owns the Maas Gallery, now on Duke St, St James.

17 EVB’s Dream Book, printed in London in 1868, contains printed pictures with accompanying poems. It should be distinguished from her unpublished Diary of Dreams, which is in possession of her relative Robert Boyle at Bisbroke Hall, Uppingham, Rutland.

18 For the séance descriptions see Wend Fenton 2, p.104.

19 Wend Fenton 2, p.62.

20 Copies of several letters from EVB to Bulwer-Lytton, written during a stay in Cannes in 1867, are in the collection of M. de Wend Fenton. Her letter to her husband Richard, written during her stay with the Lyttons in 1875, is reproduced in Wend Fenton 2, pp.80f.

21 The first printed version of the Beauty and the Beast fairytale, by Madame Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, was published in La jeune américaine, et les contes marins in 1740.

22 See poems by Alfred Lord Tennyson in Reincarnation: The Phoenix Fire Mystery, Compiled and Edited by Joseph Head and S.L. Cranston, Julian Press/Crown Publishers, inc.: New York 1977, pp.323f.

23 See Paul Goldman, Eleanor Vere Boyle as an Illustrator

The Victorian Web, literature, history & culture in the age of Victoria [Victorian Web Home

24 Wend Fenton 2, p.126.

I am very grateful to Margaret De Wend Fenton (regrettably deceased in 2017) for her great help in giving me information about EVB, along with access to her collection of EVB’s books and illustrations. And very many thanks as well to her daughters Rose Fenton and Clarissa Daulby for their helpful additions, as well as their permission to publish EVB’s pictures.